Some 1,000+ years ago, the Anglo-Saxons named September ‘Haefast Monath’ or Harvest Month. September was the time when the last of the produce was collected from the fields. Even back to the bible, that process of gathering up brought a sense of fullness and joy.

In Orange County, NY, September is still prime harvest month for onions. Corn, too, of course. Just this Monday I rolled a local cob around in some butter and chewed across it typewriter-style to great fullness and joy.

The school bus has returned to our house on weekday mornings. If I’ve managed to hustle the girls out the front door in time, we have time for a quick run around the front yard. (Just enough for the dew wet their socks.) Then,“The bus! The bus!” and a mad dash through the path nearly covered by flopped-over black-eyed Susans.

Today, as most days, I held my smaller daughter on my hip and said “look!” pointing across the road. As the bus pulled away, she could spot the window from which “sissy” smiled and waved back. It occurred to me that September always feels like this kind of happy/sad goodbye.

Is now a good time to cue the Neil Diamond? “September moooorniiiiiiiing…”

I warn you against listening to that song again (like I did). I’ve got that part of the refrain replaying in my head and I can’t stop it. The sentiment of it clashes so greatly with the rushing of breakfast, teeth, hair, socks, shoes, etc. that it’s almost laughable.

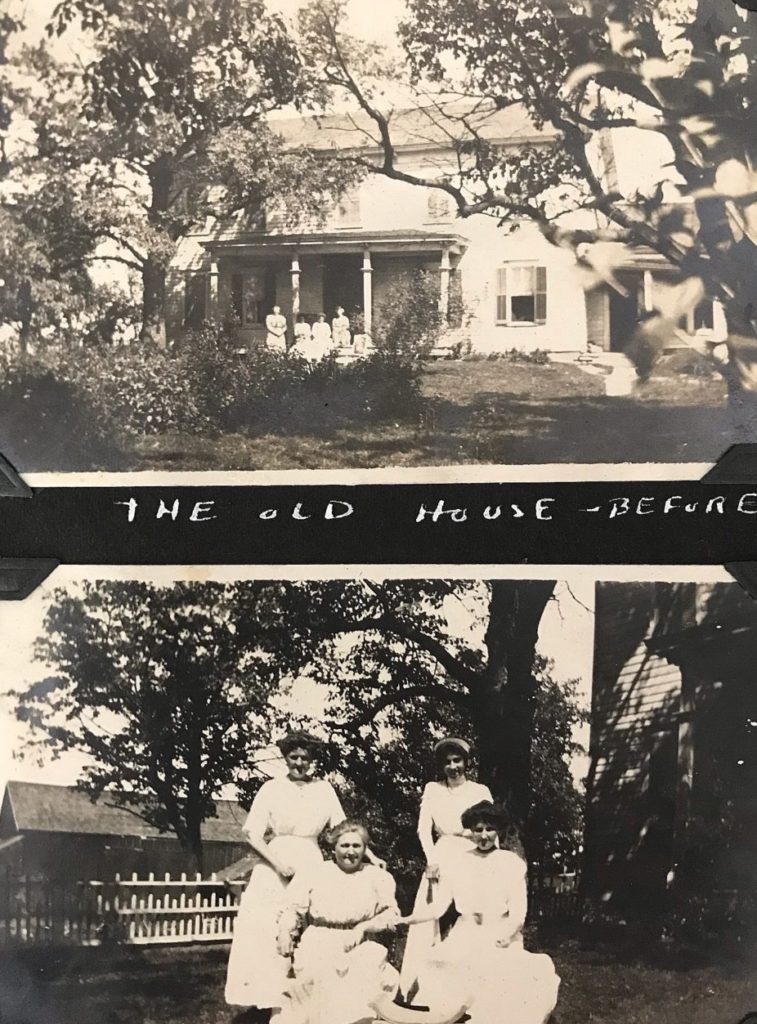

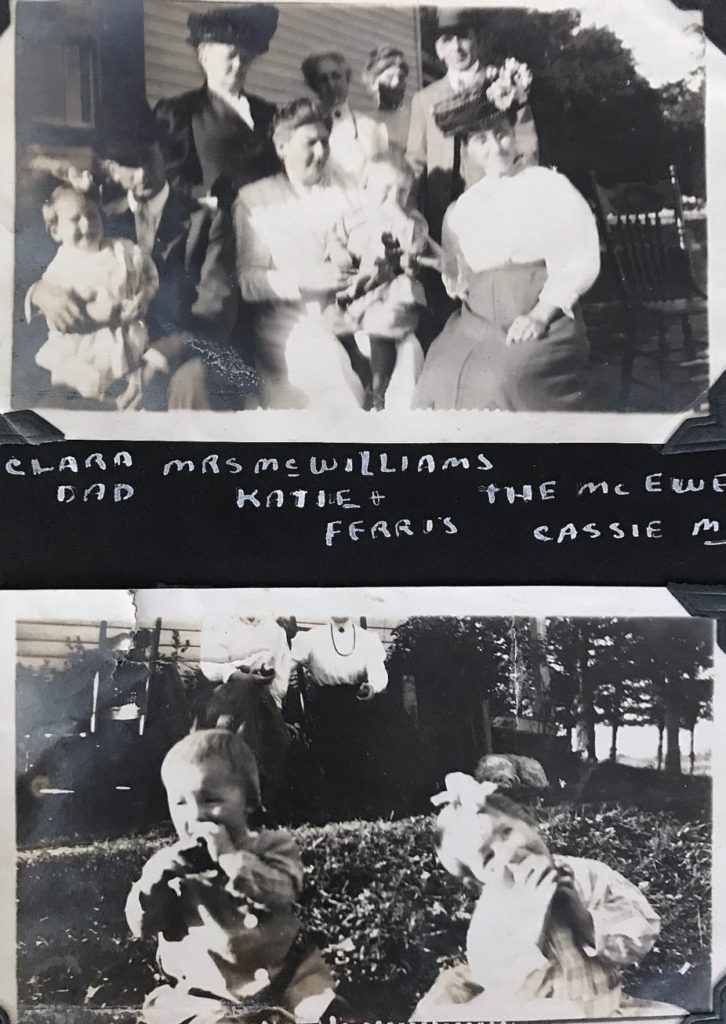

At any rate, I was talking about goodbyes when – really – today’s post is about ‘hello and welcome’. Here is a picture of the McEwens and the McMillians visiting with Eleanor, Merritt and the children some time in 1911.

Who were the McEwens?

George W. McEwen was a farmer, born in 1859. In 1906 he worked at Sunny Side Stock Farm in Mechanicstown, a fact I know only because his name appeared in newspaper advertisements selling eggs from there.

That enterprise moved to Canton, PA and in later years I find various advertisements where he’s selling cows. The address listed as R.D. 2 in Middletown which, actually, may mean he worked at Dunning Farm. Here’s an example from 1919:

FOR SALE – Registered Holstein bull and heifer calf, from 2 to 4 months old; up-to-date breeding

His wife, Mary, sits beside Aunt Kate in this picture. She was born in 1862 and married George when she was 30.

Who were the McMillians?

John Henry McMillian, born in 1847, owned a real estate and insurance business on 25 North Street in downtown Middletown. If the numbering hasn’t changed, it’s currently either a dental clinic or a nail salon called “Fancy Nails”.

He lived with his wife, Margaret (Maggie) at 14 Wickham Avenue, in Middletown. The McMillians were friends of the Dunnings through 1st Presbyterian Church. In a March 1892 newspaper, I found a note that Mr. McMillain was re-elected as elder there.

Margaret is the first person I’ve looked up who was born in a foreign country. I dug around a little to find that she came to New York from Hesse Kassel, Germany with brother, Edward Alonzo, and parents, Israel and Catherine.

By 1870, that family settled in Warwick where Israel did very well as a farmer. When he was 40, Margaret’s younger brother Edward moved in with the McMillains where he would die of an “attack of pleurisy” at the age of 47, in 1895.

Cassie, the McMillians’ daughter, has her birthplace listed as Germany too. Also a first for me, she is listed on the census as “adopted daughter”. In this picture she’s 34 and continued to live with her parents into their old age. (They still live together on Wickham Avenue as of the 1930 census: John, 83, Margaret, 77 and Cassie, 53).

How about those hats?

Aren’t they wonderful? Ladies’ hats tended to be large in 1911. (Think about the hats from the movie Titanic, only one year later). Both women’s hat styles are considered Edwardian even though King Edward passed away a year earlier.

Merritt’s hat is known as a bowler hat. According to historyofhats.net “it was favored among cowboys and railroad workers, criminals and lawman alike, because it was close-fitting and stayed firmly on the head even when the strong wind blows…” Practical, probably like the wearer himself.

Possible conversation topics?

A few months before this picture was taken, on June 22nd, 1911 King George V’s coronation took place in England. You may think that would be a distant event. In fact, when King Edward died in May they played “God Save the King” in Broadway shows and the NYSE was closed the next day (This from The Good Years by Walter Lord).

Crisco shortening came out in August 15, 1911 so maybe the ladies would have offered an opinion on using that for apple pies? The men might have talked sports. The Yankees set a record on September 20th for recording 12 errors in a double header. (Um, whatever that means).

On September 17, the first transcontinental airplane flight took place from New York to Pasadena. It took over 82 hours. Could they have imagined that someday it would only take 6 hours? After scanning our bodies and suitcases?

So that’s what I’ve managed to ‘harvest’ from that picture! As always I feel like Time, that worm, ate through the kernels ahead of me. At least I get the sense that the Dunning home was a welcoming place…always a spare chair out on the porch.

“September moooorniiiiiiiing”. Stop it, Neil. That’s enough.