Do you know that song? If you’re like me, you can sing two lines of one verse of it:

‘Mid pleasures and palaces

Though I may roam

Be it ever so humble

There’s no place like home

The song was published in 1823 and became a favorite of homesick Civil War soldiers on both sides. The tune is also played at the end of The Wizard of Oz (1939) as Dorothy repeats that line “There’s no place like home. There’s no place like home.” It’s a sentiment that any of us who grew up in a happy household can understand.

Around the time of the song’s release, Catherine Arnout and Henry Dunning (my great-great-great grandfather) set up their home (a homestead, really) near Mechanicstown, NY. They raised five boys there:

Charles Seely (born 1828)

Henry White (born 1830)

Horace (born 1833)

William Arnot (born 1839)

Edward Payson (born 1836)

Each of the brothers appear to be named after someone important at the time. Charles Seely was a well-known British politician and industrialist. Henry White was one of the founders of Union Theological Seminary (UTS) and a professor of Systematic Theology there. William Arnot was a Scottish minister and theological writer, and Edward Payson was a Congregational preacher.

Horace, my great-great grandfather? Was he named after the Roman poet? Or more likely for Horace Mann, educational reformer? Like so many other things, it’s anyone’s guess now.

What must have made Henry extremely proud (if the naming of his sons is any indication of his religious zeal) was that no less than two of them became important preachers in their own right. What’s more, his first-born, the Reverend Charles Seely Dunning, ended up marrying the daughter of Reverend Henry White (Maria Haines White) for whom his second-born was named.

I know that sounds a little crazy! I have to assume that Henry Dunning and Henry White had some sort of mutual acquaintances. Or could the world really have been so small?

Sons Henry W. and Horace grew up to be farmers. Horace inherited the homestead and Henry W. lived on an adjoining farm. Horace and wife Clarissa then raised their five children there. (My grandmother would later raise her five children there, too).

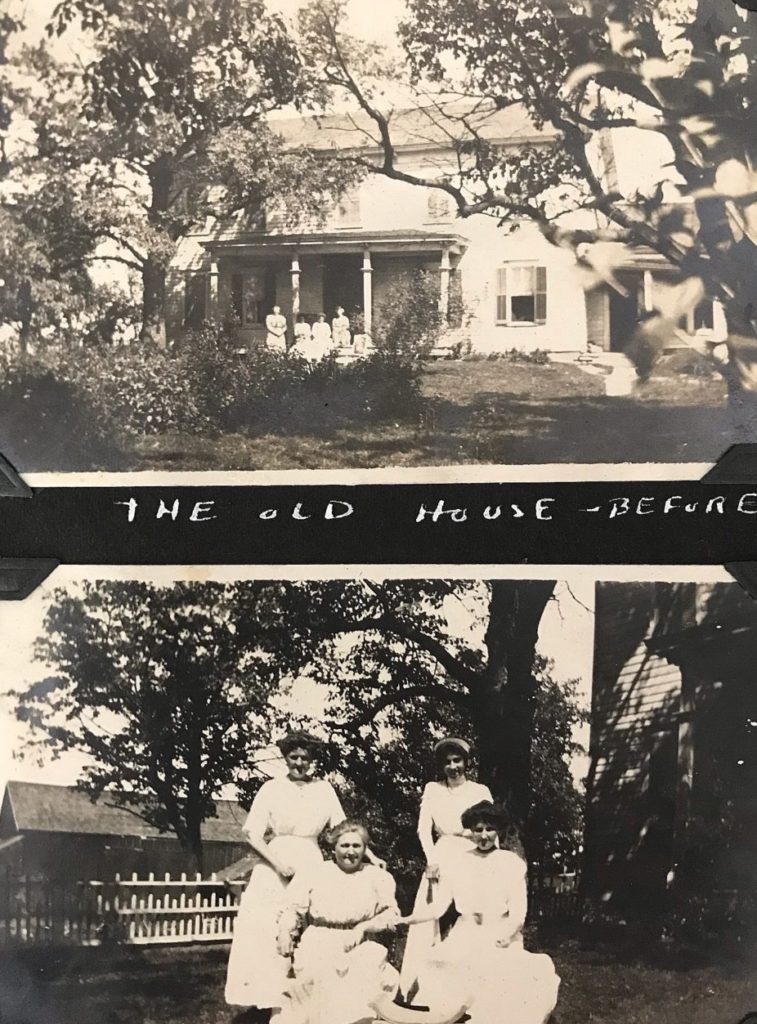

By 1911, when this photo was taken, Horace’s wife Clarissa had passed away, and two of the children had left the house. Horace Henry (1865) married Addie Gale and started up at his own farm nearby. Smith G. (1867) had settled in Ohio and started a family of his own. This, after having attended Princeton, followed by McCormick Seminary in Chicago, followed by missionary work in Africa.

In the 1910 census, only Henry Dunning (then in his 70s), and unmarried daughters Louise (47) and Kate (40) lived there. It would seem to me that the census took place just before Merritt moved there with Eleanor and took over the farm. In 1914 they will rebuild it and…you guessed it…there are renovation pictures coming.

Phew! That’s a lot of genealogy for a few paragraphs.

You may be relieved to know that besides Aunt Kate (seated on the left in the photograph) I can’t positively identify any of the other women she invited to the house. One’s last name is Jordan and another’s last name is Burrows. It was a beautiful day for a get-together.

The narrator in my book questions whether today’s generation can even understand what ‘home’ felt like for someone of our grandparents or great-grandparents’ generation:

I wonder if ever again Americans can have that experience of returning to a home place so intimately known, profoundly felt, deeply loved, and absolutely submitted to? It is not quite true that you can’t go home again. I have done it…but it gets less likely. We have had too many divorces, we have consumed too much transportation, we have lived too shallowly in too many places.

Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

Most people don’t live for generations in the same house anymore. Most people, of course, don’t have a farm to hand over. But it’s rare now to even live your entire childhood in the same place. A friend from college argued that every child should move at least once in their life: she thought the experience of change and dislocation was a good sort of ‘growing pain’.

I’m not big on pain. I feel lucky to have lived in one house my entire childhood. Even now – children in tow – there’s a “no place like home” sort of feeling when I walk in and see the bookshelf here, the sofa there. So much of our lives is virtual and changeable these days: it makes the touch and smell of an old bedroom that much more comforting.

I agree with my book’s narrator: my generation and my children’s generation may never go home again in the same way. Yet it’s also true that you can’t move forward without letting something go. Maybe we just need to learn how to live deeper wherever we find ourselves?

Writing about my grandmother’s photo album on the internet is a sort of attempt on my part. What about you?