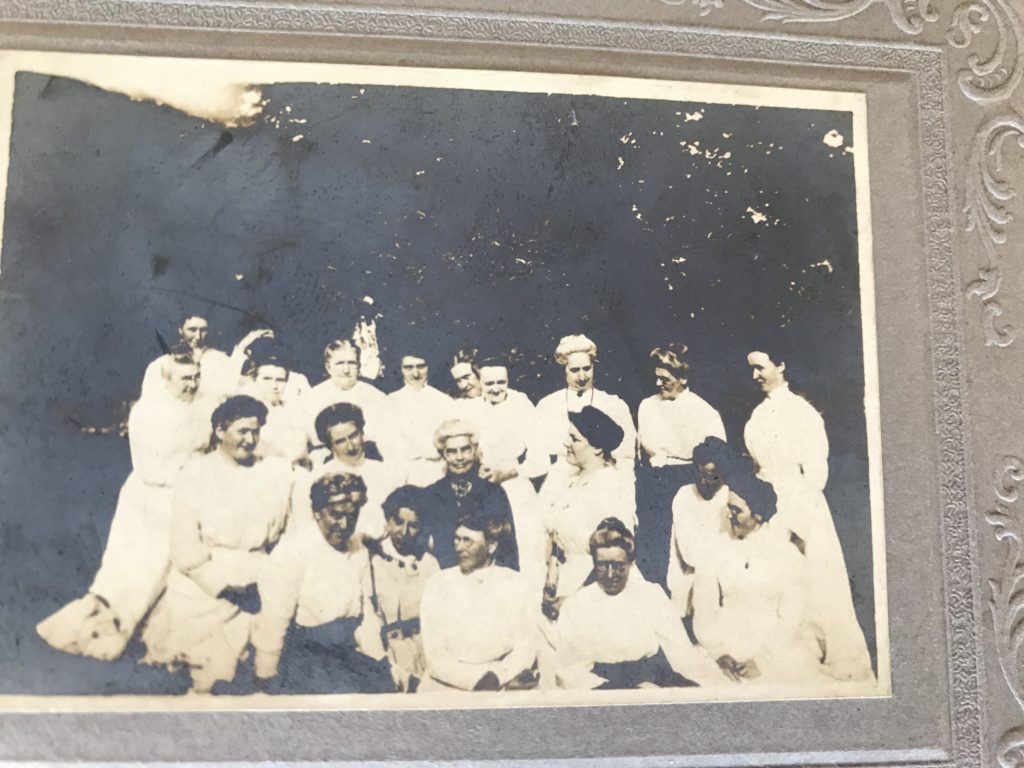

It seemed like a harmless enough picture when I started looking at it. I even saw the potential there (so many names to research!) Yet this group of ladies has confounded me.

My 7-year old’s advice was to focus on what the picture shows:

- Twenty-one ladies pose for an outdoor photograph at the home of Julia Lawrence (the back of the photo states “A Party at Julia Lawrence’s”).

- Most ladies wear similar white dresses.

- The lady in the middle, the only one dressed in black, looks as if she’s said something funny. She’s certainly drawn the interest of a couple of the women on the right. Also, she’s the only one looking straight into the camera. Her name is Kate Boak.

There’s no date on the back of the photograph but it’s 3 x 2 inches and mounted on heavy card stock with embossed detail around the border. That would put this party after 1890, presumably around 1900.

My grandmother’s sister, Clara, identified some of the people on the back of the card in her best chicken scratch.

1st row: Julia Lawrence, Eliza (Tuthuil?), Louise Dunning, Mrs. (?), Addie Dunning.

2nd row: Katharine Dunning, Eleanor Dunning, Kate Boak, Lou Hart, Addie Crawford.

3rd row: Mrs. Stephen Smith

Last 3 in 3rd row: Ella McEwen, Jessie Gale, Ella Brown

4th row: Mrs. Eugene Smith

For some reason or other, Julia Lawrence (born in England, and married to dairy farmer Charles F. as per the 1920 census in Walkill, NY) decided to have a party for twenty-one women friends. It was important enough of an event that someone took a photo and pasted it on a pretty matte border.

Where did they leave their husbands and children? Are they waiting off to the side? Was this some prelude to women’s suffrage, though still some twenty years away? A church garden party? Julia represented 1st Presbyterian Church at the International Convention in New York in July 1892 (as per the Middletown Times-Press) so that’s a possibility.

It’s all just speculation and…a little frustrating.

It reminded me of a book I read recently: A Heart So White, by Javier Marias. In one scene, a guard who has worked at the Prado museum for twenty-five years begins to play with his lighter near the edge of a Rembrandt painting.

My father was keenly aware that any man or woman who spent the day shut up in a room, always seeing the same paintings, for hours and hours every morning and on some afternoons, just sitting on a stool doing nothing but watch the visitors and watch the canvases (they’re even forbidden to do crosswords), could easily go mad, become a menace or develop a mortal hatred for those paintings.

The narrator’s father confronts the guard and asks him whether he really dislikes the painting so much. The guard says that he is “fed up” with it because he can’t see the face of the little girl properly. The narrator’s father explains that this is how the painting was painted, “with the fat one facing us and the servant girl with her back to us.”

The guard explains that this is exactly what is worst about the painting: “that it’s fixed like that forever”. He wants to know what happens next in the painting.

“But you know that’s not possible, Mateu,” he said. “The three figures are painted, can’t you see that? Painted. You’ve seen plenty of films and this isn’t a film. You must see there’s no way you’ll ever see them looking any different. This is a painting, a painting.”

“That’s why I’m going to do away with it,” said Mateu, again caressing the canvas with the flame from the lighter.

I got more and more infuriated as I searched each name in this photograph. “Lou Hart”, “Mary Lou Hart”, “Louise Hart”, “Mrs. Hart”, ” & Middletown”, “& Orange County”, on and on I went trying to divine the purpose of the party, or some connection between the women other than simple proximity.

Then I’d look at the photo again and there the ladies were, just sitting there in the same pose with that Kate Boak staring at me (is she smirking?) It did sort of make me want to set fire to the whole thing!

Then again, why the frustration? The guard goes mad asking “what happens next?” but he’s asking for something impossible and I was doing the same thing. I understand now that you can’t undertake a genealogy project expecting every picture to be part of a grand story about your past. Sometimes the answers just aren’t there.

The photos are fixed. Whether or not someone has labeled the people on them, or the place, that’s fixed. The person searching, though, is only ‘fixed’ if he insists on answering one narrow question (i.e., “why did they have this party?”) and not the million other questions that could be asked. You’re only stuck – in research and in life – if you don’t open yourself to other possibilities, to other ways of framing your situation.

My new way going forward will be to listen to my 7-year-old (at least on this point!) It was a party at Julia Lawrence’s. Twenty-one women sat down on the grass, smoothed their long skirts out and saved the moment forever.